Chinese can seem utterly alien at first to an English speaker, but these eight essential tips for learning Mandarin Chinese will help you on the way to mastering the language.

MY ETHNICALLY CHINESE FAMILY spoke neither

Mandarin nor

Cantonese at home, and I grew up in

Mississauga,

Ontario, with English as my first language. But when I was seven, my parents suddenly felt guilty their daughter had only an English tongue. I started weekly Mandarin Chinese lessons. All the other kids in class had been exposed to the language from infanthood, and just two hours of Mandarin instruction per week in my otherwise English-language existence was ineffective. Despite my best intentions, I ended up dropping out in the fifth grade.

I’m now trying to build a life in

China, and over the years have tried almost everything to become fluent in the language, including private tutors, self-study with tapes, college classes, and language buddies. Twenty years after I first set foot in my childhood Mandarin class, I’m finally on my way to mastering the language.

Here are the key lessons I’ve learned along the way. If you avoid my mistakes, and focus on the steps that really made a difference, hopefully your journey to Mandarin fluency won’t be quite so arduous or convoluted as mine.

1. Decide whether you are going to learn traditional or simplified Chinese characters.

There are two different systems of Mandarin writing – traditional and simplified. Simplified characters were created by decreasing the number of strokes needed to write the character, changing its form. For example, compare the traditional and simplified characters for fei (to fly):

Traditional: 飛

Simplified: 飞

Today, traditional Chinese characters are mainly used in

Hong Kong,

Macau, and

Taiwan. Simplified characters were introduced in China in the 1950s and 60s to increase literacy rates, and are the official system of writing in mainland China, and

Singapore. This is also the form of writing taught in Mandarin courses around the world.

Chinese calligraphy. Image:

Aplomb

People debate whether it’s better to learn the more complicated but beautiful traditional Chinese script, or to follow the widely used simplified version. I think it’s a personal choice, and depends on where you want to live and why you are learning Mandarin. Do you want to live in mainland China? Do business in

Shanghai? Learn Chinese culture and history? Teach in Taiwan?

It is possible to learn both, but as a beginner you should stick to one system to avoid confusion. I started out with teachers who used textbooks with traditional characters from Hong Kong, but I had to learn from a simplified

Beijing syllabus in university. It sometimes felt like I was learning to write a new language. Personally, I wish I had always learnt the simplified script, since my goal was to live and work in mainland China.

2. Invest time and money in an intensive Mandarin program so you have a solid foundation.

This is applicable to most languages, but intensive learning at the beginning is particularly important for a language like Mandarin, which is utterly alien to an English speaker.

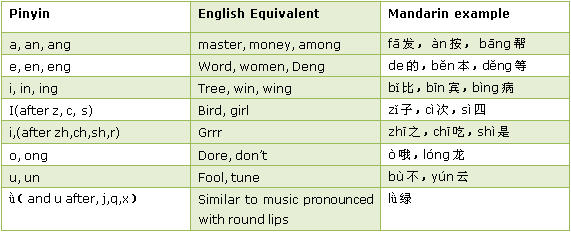

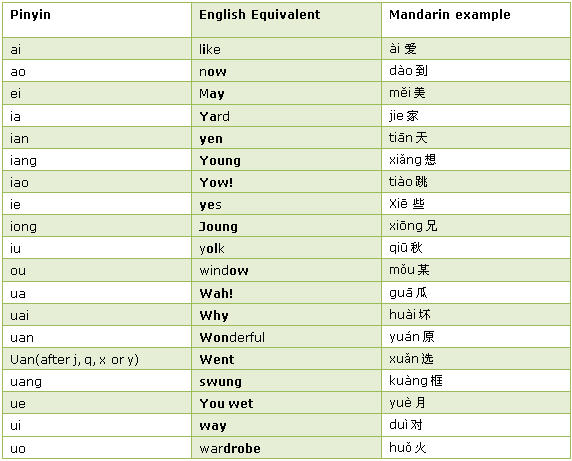

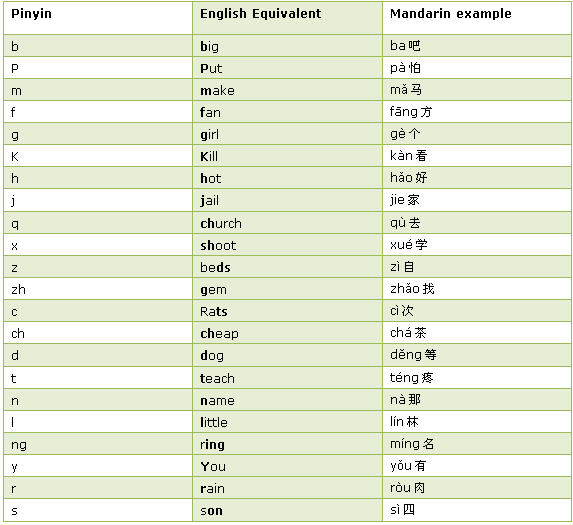

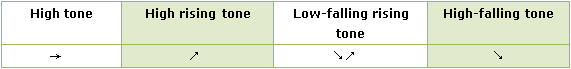

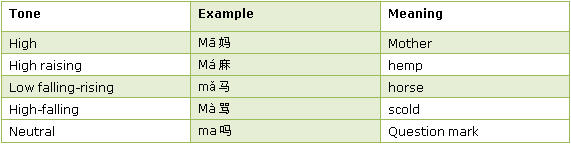

I failed to learn Mandarin as a child because two hours a week were not enough to build the foundation. For Chinese, the basics are crucial: you must learn the four tones (which are often indistinguishable to English speakers), master the

Pinyin needed to pronounce the logographic characters, and grasp other fundamentals such as the stroke order to form the characters.

It takes hours of writing, listening, and speaking to master these basics. A British-Italian friend of mine studied once a week at a Confucius Institute in London for eight months with no results. After only a month of intense classes at Mandarin House in Shanghai – six hours a day, five days a week – she was writing and speaking like a Chinese five-year-old, which is progress not to be taken lightly. She then switched to a less intense daily program, but credits her “Chinese boot camp” for giving her a great foundation to work from. Even one-on-one tutoring may not be effective if it isn’t a daily ritual.

Check out

GoAbroad.com for a good list of schools and programs in China.

3. Become language buddies with non-English speakers who are learning Chinese.

People learning Chinese who aren’t native English speakers are great language partners:

1. They are students like you, so you may feel less embarrassed making mistakes with them.

2. You are less likely to fall back on English to communicate.

Swapping English for Chinese as part of a language exchange with locals is fine – but with my

Japanese and

Korean classmates, Chinese is often our only common language, so

we speak it all the time. There is no need to structure our sessions. We hang out after class when the material is fresh in our minds, and use all the words and idioms we’ve just learned. I don’t worry too much about being right or wrong, but focus on just opening my mouth and trying to use the language as much as possible, without English to fall back on.

4. Follow a Chinese TV show you like, or listen to Chinese music.

Consuming Chinese pop culture is an enjoyable way to build your vocabulary just by sitting on your tush, and a great chance to test your listening and comprehension away from the classroom syllabus.

What you should watch or listen to depends on your preferences and language level. I’m a child at heart and a big cartoon fan, so I’ve gotten hooked on

Xǐ Yáng Yáng yǔ Huī Tài Láng(

“Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf”), an outrageously popular Chinese animated TV series. It’s intensely cute, and easy for anyone with a basic grasp of Mandarin to follow.

I suggest focusing on just one particular show or mini-series to start with. I find I get emotionally involved with the storyline, which gives me added incentive to keep watching, and it helps my listening skills to focus on the accents of only a handful of people. One of my favorite dramas was a 2005 Taiwanese series called “The Prince Who Turns into a Frog.” With each passing episode I grew increasingly familiar with the characters’ voices, and it became easier to understand their dialogue.

5. Practice speaking in front of a mirror.

In my last Chinese class, I realized that many silent students were nervous about talking because they thought they looked awkward when they spoke. And it’s true, something happens to my mouth when I speak Chinese – it moves in crazy ways that it doesn’t when I speak English. Sometimes, if I become aware that I’m speaking fluently without a book or script, I start to overthink my words and the movements of my mouth, and I begin to falter.

It’s just as important to be physically confident about speaking Chinese as it is to have a strong grasp of the vocabulary, pronunciation, and tones. Speaking in front of a mirror and seeing how your mouth forms Chinese words can help with this. Watch yourself speak, relax your facial muscles, and practice being angry and sad and happy in Chinese. When you realize you don’t look like a fool, fluency will start to come naturally.

6. Surf the Chinese Internet.

Eschewing English-language social networks in favor of their Chinese equivalents gives you a good reason to use Chinese characters on a daily basis, as well as the opportunity to network with a large community of Chinese netizens. Facebook and Twitter are blocked in China at the moment, but you can use their local equivalents,

Renren and

Weibo.

I used to be wildly frustrated when learning Chinese characters because I saw it as too much work for too few immediate rewards. But I remember the day my iPod Touch arrived at my door, after I’d ordered it online having spent the previous day struggling to read Chinese terms and conditions. When the right product turns up at your home, it’s tangible proof you can use your Chinese skills!

I still find

Taobao, the Chinese equivalent of eBay, difficult to navigate because of the cluttered interface and overwhelming array of products, but I can now use

Amazon.cnwith no problems, as the layout is similar to the English-language version.

7. Take the HSK, a standardized Mandarin exam for non-native speakers.

The Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì (HSK) is a Mandarin proficiency exam administered in China and abroad. There are six possible levels of achievement, the most elementary testing you on 150 words, and the most advanced testing your knowledge of up to 5000 words.

Some people take the HSK for Chinese university admission, others because they are hoping for a short-term language study scholarship. For those of us with only vague plans what to do with our Mandarin skills, I suggest taking it as an end goal. It’s often easier to push yourself if you’re working towards something concrete.

The exam tests your listening, reading, comprehension, and composition skills. The cost depends on your level. The spoken part of the exam is separate. For more details, check out the

website.

8. Live in China a while, but don’t immerse yourself in English-speaking expat circles.

I live in Shanghai, and many foreigners tell me this is not the best place to learn Mandarin. “Get out of the big city and move somewhere more rural and really Chinese,” they argue. But I disagree that camping out in a tiny city is necessarily the best way to learn Chinese. You can be in a big city and speak Mandarin everyday, or go to a rural town and seek out the five other English-speaking foreigners there.

Last year I lived in the Yangpu district of Shanghai, far away from the “foreigner-infested French Concession,” as my friend joked. Yet I surrounded myself with English speakers, and my Chinese didn’t improve. This year, I’m actually living in the “foreigner-infested French Concession”, but I feel more immersed in the language. I speak Chinese to my Japanese and Korean classmates, to my landlord, to my elderly neighbors, to my favorite restaurant owners, to Chinese friends. I live in one of the most foreigner-friendly parts of China, yet I’m doing better than ever with the language.